TL;DR

- Over 300,000 workers, mostly private contractors, clear snow across the US.

- The industry generates $20-23 billion annually with high client retention.

- Labor shortages and aging workforce challenge service levels.

- Technology like GPS and autonomous plows is transforming operations.

- Pay is modest despite hazardous conditions and liability risks.

Introduction

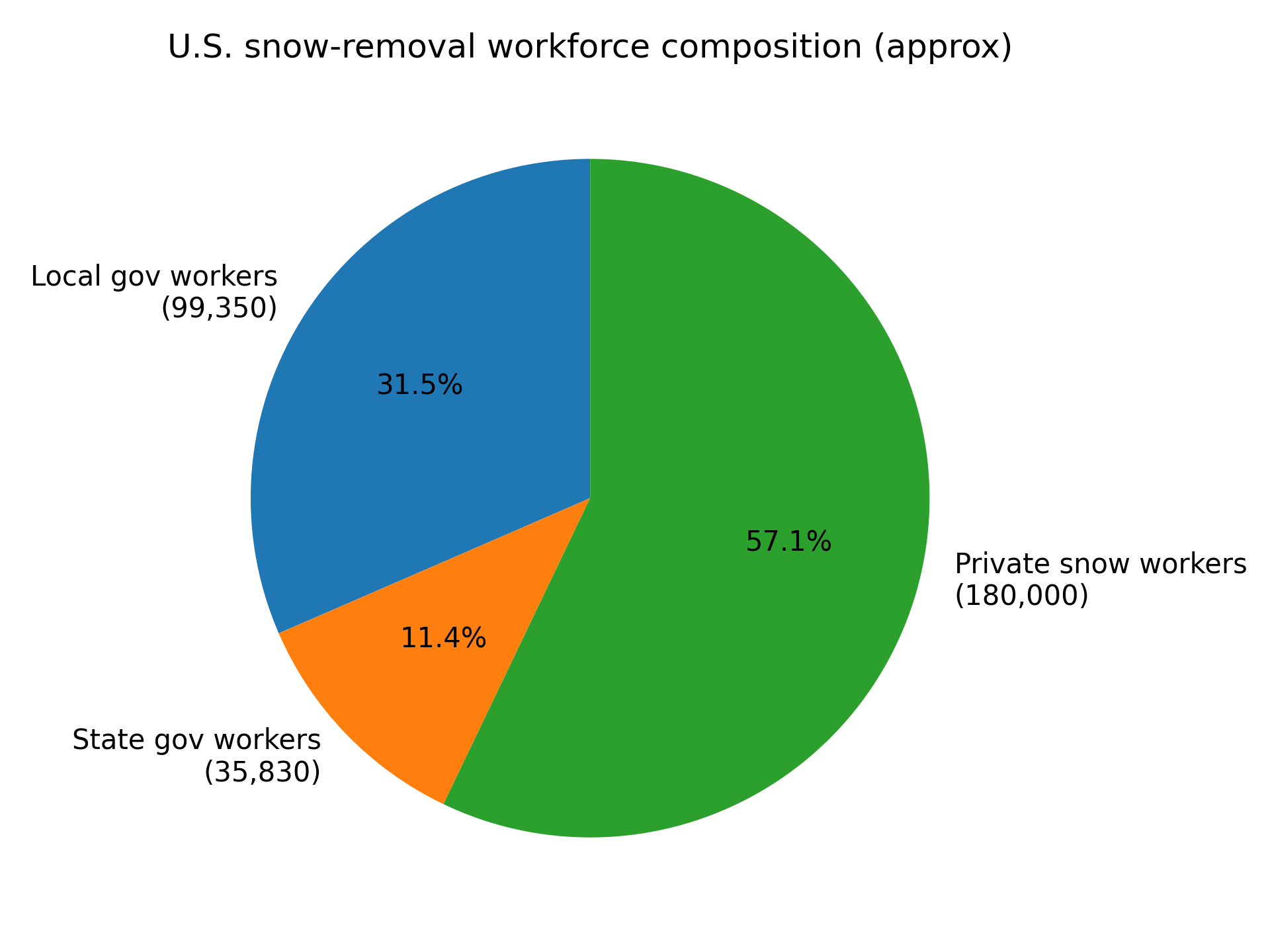

Every winter, before the morning commute begins, an army of plow operators rumble onto America’s roads and parking lots. According to estimates from the Snow & Ice Management Association (SIMA), more than 180,000 workers earn their livelihood pushing snow and spreading salt[1]. Add in public‑sector highway maintenance crews and the number climbs past 300,000 people. Yet most of us never see these people - and few realize that the majority do not work for city transportation departments. Private contractors, family‑owned landscaping businesses and seasonal crews clear the bulk of America’s roadways, often working through the night in dangerous conditions for modest pay. This feature looks behind the plows to reveal who actually clears the snow, how the industry is structured, what it costs to run a plowing operation and why labor shortages and new technology are reshaping the job.

Key Takeaways

| Metric/Insight | Evidence & data | Key takeaways |

|---|---|---|

| Public vs. private workforce | BLS counts 143,330 highway‑maintenance workers, mostly local and state government employees[3]. SIMA estimates 180,000 private snow workers[1]. | Roughly 45 % of U.S. snow‑removal workers are public employees, while 55 % work for private contractors and small businesses. The private sector’s size demonstrates how dependent cities are on outsourced plowing. |

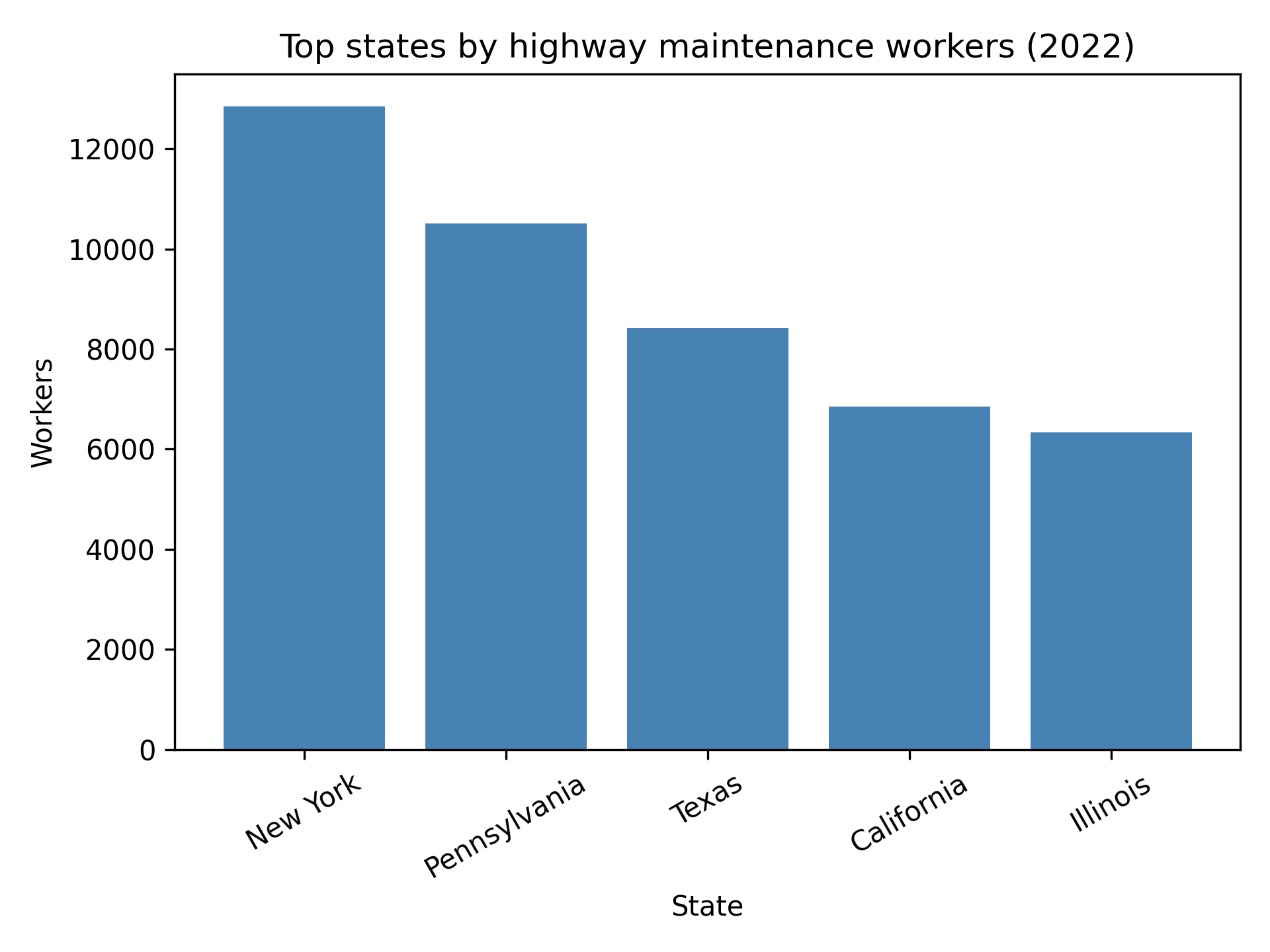

| Regional job concentration | New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, California and Illinois have the highest numbers of highway‑maintenance workers[3]. IBISWorld notes that the Mid‑Atlantic region hosts the most plowing companies[2]. | Jobs cluster in the snow belt. Dense urban centers like New York produce the highest employment, while Mountain states rely heavily on seasonal operators. |

| Pay vs. risk | Mean annual wage for highway‑maintenance workers was $45,790[3]; private plow drivers average $38,842[5]. Slip‑and‑fall claims cost $33k—$45k[1][11] and winter road accidents cause 1,300+ deaths and 116,800 injuries yearly[17]. | Snow‑plow drivers earn modest wages despite working long hours in hazardous conditions and facing liability risks that can exceed their annual earnings. |

| Economic contribution | Private snow‑and‑ice management industry generates $20.8—$23 billion in revenue[1][2]. Average business earns $152k (single‑service) or $435k (multi‑service) per year[1]. | Snow removal is a multi‑billion‑dollar industry that sustains thousands of small businesses and supports local economies during winter. |

| Growth trends | Industry revenue grew about 2.5 % per year from 2016‑2022[1] and is projected to grow 4.3 % annually through 2025[2]. SIMA notes rising adoption of GPS and telematics[22]. | Demand for snow services is rising, but labor shortages threaten service levels. Technology (GPS, remote operation) is being adopted to optimize routes and attract new operators. |

| Under‑reported insight | SIMA’s survey shows that only 15 % of operators focus primarily on snow; most rely on landscaping or construction in warmer months[1]. Additionally, only 9 % of companies are experimenting with electric or alternative‑fuel plows[24]. | Most plow drivers are not career snow professionals; they pivot between seasonal gigs, underscoring the gig‑economy nature of the job. The transition to electric or autonomous plows is in its infancy, suggesting a major opportunity for innovation. |

America’s Snow‑Removal Workforce, by the Numbers

Workforce size and composition

-

Total workforce: Industry research commissioned by SIMA estimates that the private snow‑and‑ice management sector employed about 180,000 workers in 2024/2025 and generated $20.8 billion in revenue[1]. IBISWorld’s 2025 snow‑plowing services report puts the industry even higher at 235,000 employees and $23 billion in revenue, served by roughly 114,000 businesses[2]. Meanwhile, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported 143,330 highway‑maintenance workers (public employees who plow roads, patch potholes and do other road work) in 2022[3].

-

Municipal versus private workers: Highway‑maintenance employees are predominantly public‑sector - roughly 99,350 workers were employed by local governments and another 35,830 by state governments[3]. Private plowing accounts for the remainder. Combining BLS data with SIMA’s estimate suggests that roughly 310,000 people work in snow removal, with public employees (government) making up about 45 % of the workforce and private contractors and small business employees roughly 55 %. The pie chart below visualizes this split.

-

Businesses and market share: SIMA counted about 88,200 snow‑removal businesses in 2022 and noted that the industry is extremely fragmented - the four largest companies collectively hold just 5 % of the market[1]. IBISWorld reports 114,000 businesses in 2025[2], reflecting growth as new contractors enter the market. Nearly half of snow companies also offer lawn‑and‑landscape services, making plowing a critical winter revenue stream[1].

Regional concentration

Snow‑removal jobs are heavily concentrated in the Midwest and Northeast, where lake‑effect storms and Nor’easters can dump feet of snow at once. BLS employment data show that New York (12,850 workers), Pennsylvania (10,510), Texas (8,420), California (6,850) and Illinois (6,330) had the highest numbers of highway‑maintenance workers in 2022[3]. The chart below illustrates these concentrations.

IBISWorld identifies the Mid‑Atlantic states (especially New York and Pennsylvania) and parts of the Upper Midwest as having the most snow‑plowing companies because they receive frequent snowfall and have dense populations[2]. Mountain states like Colorado and Utah also employ significant numbers of plow operators due to alpine resorts and interstate passes.

Typical crew structure

Surveys of SIMA members provide insight into how private operators run their businesses. A “typical provider” reports working 13—16 plowing events and 20—25 de‑icing events per season, serving around 66 accounts across 100 properties[1]. About 35 % of revenue comes from snow and ice services (the remainder is often landscaping), and only 15 % of operators focus exclusively on snow[1]. Most businesses are small: sole proprietors or crews of fewer than 10. However, large regional firms like New Hampshire‑based Outdoor Pride manage “zero‑tolerance” facilities and operate over 300 machines, including 85 Bobcat skid steers equipped with AutoWing plows[4].

The Private Plow Economy

Revenues and growth

SIMA’s research estimated that snow‑and‑ice management generated $20.8 billion in revenue in 2024/2025, up from $18 billion in 2016 --- a growth rate of roughly 2.5 % per year[1]. IBISWorld forecasts a 4.3 % annual growth for snow‑plowing services through 2025, reaching $23 billion[2]. Major revenue segments include commercial (60 %) and residential (40 %) accounts[1], with industrial and retail properties accounting for the largest shares of commercial work. Providers report exceptionally high client retention (about 93 %[1]), reflecting the importance of reliability in winter storms.

Earnings and contract values

Pay for snow‑plow operators varies widely. BLS data show that highway‑maintenance workers earned a mean annual wage of $45,790 (about $22 per hour) in 2022[3]. Zippia’s 2025 survey of private plow drivers found an average salary of $38,842 ($18.67 per hour), with experienced operators earning over $52,000[5]. However, when storms hit, many private drivers are paid per event or per inch of snow rather than by salary. An Idaho Capital Sun report on the 2021 labor shortage noted that some Massachusetts municipalities offered $115—$200 per hour for private drivers with their own trucks[6].

Municipal contracts often pay higher hourly rates to secure trucks quickly. In West Orange, New Jersey, a recent bid document listed $250 per hour for F‑450 plow trucks and $300 per hour for F‑700 trucks[7]. Larger loaders commanded up to $350 per hour[7]. On the commercial side, snow‑removal companies typically charge $25—$75 per hour for shoveling, $30—$100 per visit for plowing and $20—$65 per application for salting[8]. Seasonal contracts for small parking lots average $290—$450 per year[8]. These figures underscore the variability of earnings and the importance of intense storms for profitability. In the words of one plow driver quoted in a regional news piece, “Snow is money falling from the sky”, because revenue is tied directly to storm frequency.

Cost pressures

Running a plow business requires substantial capital. A contractor‑grade plow costs $3,000—$6,000, and professional operators often replace plows every three years[9]. Constant plowing wears down truck transmissions (around $3,500 to replace) and often necessitates new pickup trucks costing over $50,000[10]. Spreading salt can cost over $1,000 per season for a small lot[10]. Insurance adds another layer: commercial auto coverage runs $1,000—$3,000 per vehicle per year, workers’ compensation $2,000—$6,000 per employee, equipment coverage 1—3 % of equipment value and general liability about $1 per day. Slip‑and‑fall lawsuits average $15,000—$45,000 per claim[10][11], so contractors must document every push and application of salt to defend against litigation. These costs highlight why only a handful of firms operate as full‑time snow businesses and why many plow drivers also run landscaping crews in warmer months.

Voices from the field

Labor shortages have exacerbated cost pressures. In a 2021 interview with Stateline, Rick Nelson of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) explained that state DOTs lacked “bodies to put in plows” and were competing with freight companies for commercial drivers. He described plowing as a difficult job that requires a commercial license and the ability to control the plow, salt and sand simultaneously[12]. Another official, Barbara LaBoe of the Washington State DOT, warned that shortages meant some roads could not be plowed as quickly and crews were “working 24‑hour shifts” to keep up[13]. Private contractors echo these challenges. Christopher Cronin, Andover, Massachusetts’s public works director, told the Boston Globe that plow drivers are getting older and rising costs have made it harder to recruit new ones[14]. Jordan Smith, owner of Storm Equipment, sees technology as a solution: he partnered with Teleo to retrofit plows for remote and autonomous operation, arguing that supervised autonomy “opens the door for people who wouldn’t normally operate heavy equipment” and delivers “undeniable value” for contractors[15]. Meanwhile, Degen Kelly, director of operations at Outdoor Pride, says investing in high‑quality attachments and equipment pays off: by “crunching the numbers,” operators realize they can eliminate redundant machines, work faster and extend equipment life[16].

The Economics of Snow Clearing

Pay versus risk

Although pay rates can spike during big storms, the work remains perilous. The Federal Highway Administration estimates that snowy or icy pavement causes more than 1,300 deaths and 116,800 injuries on U.S. roads annually[17]. For snow‑removal workers, slip‑and‑fall claims are common; SIMA’s impact report found a 1‑in‑6 chance that a contractor will face such a lawsuit each season, with average claims around $33,000[1]. Insurance data indicate that winter slip‑and‑fall claims cost $40,000—$45,000 and contribute to 95 million lost workdays[11]. Yet the average private plow driver earns less than $40,000 a year[5], illustrating a stark imbalance between risk and compensation.

Seasonal revenue swings

The industry’s revenue is highly weather‑dependent. SIMA reports that the average single‑service snow business earns $152,000 annually, while companies that combine snow with landscaping average $435,000[1]. Snow services typically account for 35 % of annual revenue[1]. Revenues fluctuate based on the number of storms; one SIMA survey noted that providers handle 13—16 plowing events per season[1]. Businesses must budget for lean winters and rely on retainer fees to remain solvent.

Labor Shortages and Safety Risks

A shrinking labor pool

Multiple factors have converged to create a shortage of snow‑plow drivers. Retirements, vaccine mandates, and the lure of better‑paying trucking jobs left Montana with half its normal temporary plow drivers, Kansas missing 30 %, and Pennsylvania needing 60 % more seasonal drivers during the 2021—2022 winter[18]. Seasonal work requires crews to be on call around the clock and willing to work 12‑hour shifts in hazardous conditions[19]. State DOTs have offered signing bonuses and raised base pay - Colorado boosted wages and added a $2,000 snow‑season bonus, while Massachusetts towns offered $115—$200 per hour to private drivers[6]. Yet officials like Rick Nelson say the job still demands “a special kind of person who wants to go out in a blizzard and plow”[20].

Injuries and fatalities

Beyond traffic accidents, plow crews face slip‑and‑fall hazards, carbon‑monoxide poisoning, heart attacks and injuries from heavy equipment. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) issued a hazard alert after investigating fatalities related to snow‑removal work on roofs, urging employers to provide fall protection and training[21]. Public data on snow‑removal fatalities are limited, but the broader winter‑weather statistics underscore the risks.

Technology and the Future of Snow Removal

Route optimization and telematics

Modern snow fleets are increasingly connected. SIMA reports that 70 % of large snow operators and 35 % of small operators now use GPS fleet tracking and telematics to monitor plows, dispatch them efficiently and document service for clients[22]. Cities such as Syracuse, New York, have developed public Snow Operations Maps that integrate fleet data from Samsara, ESRI and Rubicon to show when a street was last plowed, improving transparency and accountability[23]. New York City’s Department of Sanitation (DSNY) upgraded its Bladerunner system and invested nearly $500 million in new plow trucks, resulting in its highest headcount in decades[23].

Electric and autonomous plows

The next frontier involves electrification and automation. A 2024 survey found that only 9 % of operators had explored electric or alternative‑fuel plows, largely due to battery‑heating issues that make winter operation challenging[24]. Companies such as Teleo and Storm Equipment have begun retrofitting skid‑steer loaders with remote‑operated and autonomous plow systems. Owner Jordan Smith says such technology offers “undeniable value” and could enable people without heavy‑equipment experience to operate plows safely from warm offices[15].

Data‑driven decisions

Advanced analytics also help crews decide when to deploy salt versus plows. Providers like KBS use SnowMap forecasting tools to generate automatic work orders when snowfall thresholds are met[11]. These digital logs help contractors defend against slip‑and‑fall claims and refine resource allocation. Some municipalities are experimenting with heated roads and alternative de‑icing chemicals to reduce salt usage and environmental impacts[22].

What Cities Pay - and Who Gets the Contract

Procurement and outsourcing

Most municipalities maintain a core fleet of plow trucks and operators but outsource additional routes to private contractors during large storms. Requests for Proposals (RFPs) typically specify hourly rates for different types of equipment (e.g., F‑450 truck, loader, skid steer) and require contractors to have liability insurance and maintain detailed logs. The West Orange contract noted above paid $250—$300 per hour for plow trucks and $275—$350 per hour for loaders[7], illustrating how municipal rates outstrip typical commercial charges.

Federal and state assistance

Extreme snowfalls can overwhelm local budgets. When a blizzard in December 2022 dumped up to six feet of snow on Buffalo and neighboring communities, New York governor Kathy Hochul secured a major disaster declaration, allowing federal reimbursement for snow‑removal operations[25]. However, FEMA’s existing guidelines only fund snow removal after “record or near‑record snowfall over 1—3 days”[26]. In response, Congressman Tim Kennedy introduced the SNOW Act in 2024/2025 to treat blizzards like other disasters. His bill would remove outdated snowfall thresholds, “unlock Individual Assistance for snow disasters,” add snow‑removal equipment to FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and raise the federal cost share to 90 % for rural or low‑income communities[27]. Local officials say such reforms would help small towns afford plow contracts when storms paralyze their economies.

Conclusion

From the Rocky Mountains to the Atlantic coast, America’s snow‑removal apparatus is far larger and more complex than most drivers realize. An estimated 300,000 people - roughly split between public road crews and private contractors - mobilize each winter to keep commerce moving. Yet the job remains precarious. Plow operators often work 12‑hour shifts in blinding storms for wages that barely crack $40,000 a year[19][5]. Equipment and insurance costs are high, and the risk of lawsuits or accidents can wipe out profits[10]. Meanwhile, climate‑driven megastorms and an aging workforce are stretching municipal budgets and creating persistent labor shortages.

The industry’s future may hinge on two forces: innovation and policy. GPS tracking, route optimization and remote‑operated plows are already improving efficiency and attracting a new generation of operators[15][23]. At the same time, legislation like the SNOW Act seeks to modernize FEMA’s assistance rules so communities aren’t bankrupted by once‑in‑a‑century blizzards[27]. Recognizing the size and significance of this hidden workforce - and compensating it appropriately - will be essential for keeping America’s roads open during increasingly volatile winters.